Items related to Mentors, Muses & Monsters: 30 Writers on the People...

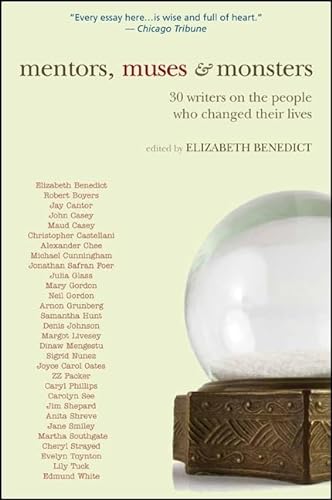

Mentors, Muses & Monsters: 30 Writers on the People Who Changed Their Lives (Excelsior Editions) - Softcover

In therich, impassioned essays collected here, thirty of today's brightest literary lights address the question of mentorship and influence, exploring those times in their development as writers when a special person, a beloved book, or a certain job gave them the courage to take a bold chance on their own gifts. For Jane Smiley, the turning point was the support of her fellow classmates--not her teachers--at the famed Iowa Writers' Workshop. For Jonathan Safran Foer, it was a brief encounter with Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai. For Michael Cunningham, it was an illicit cigarette break with a tough-talking teenage girl at Hollywood High who challenged him to read Virginia Woolf. And for Elizabeth Benedict, inspiration came after writing an essay about her Barnard mentor, Elizabeth Hardwick, after she died in 2007.

In drawing together these essays, Benedict found dozens of writers eager to tell the stories of their own influences. As most of these encounters occurred when the writers were young--unsure of who they were or what they could accomplish--many of these essays radiate a poignant tenderness, and almost all of them express enduring gratitude. Rich, thought-provoking, sometimes funny, and sometimes heartbreaking, these portraits of the artists as young men and women illuminate not only the anxiety but the necessity of influence--and the treasures it yields. Thirty essays--and thirty dazzling paths to creative awakening and literary acclaim.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The response to my invitation was overwhelming. One after another, in e-mails, on the phone, and in person, in a matter of weeks, two dozen fiction writers said yes, they wanted to contribute to this anthology. Some days I would hear from two or three or four people, saying yes, count me in. Of course, I was delighted—and slightly flabbergasted by the wellspring of enthusiasm. I seemed to have hit a nerve.

Several knew right away whom they wanted to write about—Mary Gordon on Elizabeth Hardwick and Janice Thaddeus, Jay Cantor on Bernard Malamud, Lily Tuck on Gordon Lish, Jim Shepard on John Hawkes. But quite a few said yes, emphatically, without knowing their subject for sure. Early on, Jonathan Safran Foer was deciding from among Joyce Carol Oates, with whom he studied at Princeton, the artist Joseph Cornell, whose famous boxes enchanted him at a young age, and the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai. At first, Margot Livesey wasn’t sure whether to choose her adopted father—an English teacher at a Scottish boarding school—or a long-dead muse.

In saying yes before they had settled on a subject, I picked up in writers’ voices and in their e-mails a yearning to acknowledge and to thank the people who had made a landmark difference in their lives—to recognize them the best way a fiction writer can, by telling the story of their association. Because most of these encounters occurred when the writers were young and vulnerable—uncertain about their identities and what they were capable of—some of the pieces have a sweetly aching quality, and nearly all of them express abiding gratitude. But sweetly aching or not, a good many of the writers are looking back at themselves at a tender age when something powerful happened to them, a moment when an authority figure saw talent in them, or when they came to believe they possessed it themselves—and their wobbly lives changed direction and velocity. They knew, in a way they hadn’t before, where they were headed; and what is more potent, and more moving, than that? It’s like being rescued. No, it is being rescued—from uncertainty, indecision, mediocrity.

Life brings us emotional experiences to compete with that one in intensity, but the others invariably involve romance, children, family ties, two-sided associations that inevitably become messy, fraught, downright imperfect. But the feelings of gratitude a student or supplicant usually has for a mentor have an aura of purity about them—uncluttered, unalloyed gratitude—that’s absent from most other intense relationships. It’s fitting that we idealize our mentors. They are more accomplished than we are; they are in a position to bestow feelings of worth on us that carry more weight in the real world than praise from even the most ardent parents. Their praise counts for something out there—and because of that, it also counts in here, where we live and work and proceed with nothing but whatever talent we possess, whatever nerve we can summon, and the knowledge that the only way to get to Carnegie Hall, or its literary equivalents, is practice, practice, practice, which is to say, write, rewrite, rewrite.

Mentors are our role models, our own private celebrities, people we emulate, fall in love with, and sometimes stalk—by reading their books compulsively. In her essay on Alice Munro, Cheryl Strayed writes, “I love Alice Munro, I took to saying, the way I did about any number of people I didn’t know whose writing I admired, meaning, of course, that I loved her books.... But I loved her too, in a way that felt slightly ridiculous even to me.” When things go well, we are the beneficiaries of our mentors’ best selves, not just their admirable writing but the prescient insights that divine talent in us before we know it’s there ourselves.

Alongside the mentor’s noticing us, much of the force of our feelings is revealed in how much energy we invest in noticing the mentor; but what would you expect from writers obsessed with other writers? Obsession is an occupational hazard. Or do I mean an occupational necessity? In his essay on Annie Dillard, Alexander Chee writes, “By the time I was done studying with Annie, I wanted to be her.” He wanted her house, her car, and most of all, a boxed set of the books he had not yet written, like the boxed set of her books he admires in a store. When she was in her twenties, Sigrid Nunez lived with her boyfriend and his mother—Susan Sontag. In her essay “Sontag’s Rules,” in crystalline detail, she remembers Sontag’s elaborate rules for living the life of a writer and intellectual—and Nunez names each rule she adopted for herself. In the more complicated case of Maud Casey, whose influences are the writers John Casey and Jane Barnes—who happen to be her parents—she admits that as a child, she imagined that she would grow up to be her parents, and that until she went to graduate school, she could not read a novel, any novel, without hearing their voices in her head.

Not all writers have quite such complicated relationships with their mentors or mentor equivalents. John Casey, father of Maud, had an unfraught, collegial relationship with Peter Taylor after they met while Casey was a law student taking a creative writing class on the side. Julia Glass writes a glowing paean to her longtime book editor and muse Deb Garrison, and tells us, along the way, how she herself went from being a painter to a novelist rather late in life. Carolyn See honors an unlikely pair of influences, an English professor whose lectures on poetry she attended for three weeks when she was twenty, and her beloved, eccentric father, who had always yearned to be a serious writer; the closest he came was writing seventy-three books of pornography near the end of his life.

Joyce Carol Oates answered my invitation by telling me that her mentors had been Emily Dickinson and Ernest Hemingway and several contemporary writers she had never known. I replied that it would be fine to write about mentors of that kind—to which Oates replied with an essay far more ambitious and illuminating, “On the Absence of Mentors/Monsters: Notes on Writerly Influences,” that includes stories of her friendships with Donald Barthelme and John Gardner—and her childhood passion for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass.

Other writers arrived with more unconventional sources of inspiration. The distinguished critic Robert Boyers, who found his fictional voice at fifty, is indebted to the Italian writer Natalia Ginzburg, because of his poet wife’s connection to her. Evelyn Toynton, an American who lives in England, recalls the sorrows of her beloved handicapped mother, who showered Toynton and her sister with books and stories about English kings and queens when they were sorrowful children in New York City, on their twice-monthly visits to their mother’s shabby, book-filled apartment. The story of Arnon Grunberg’s literary awakening as a high school dropout in Amsterdam is so exotic—and funny and heartbreaking—that I am loath to try to summarize it in a sentence. Edmund White’s portrait of the late Harold Brodkey, set in gay New York in the 1970s, provides the anthology its single full-blown “monster.” Monstrous though he was, White acknowledges his writerly debt to Brodkey.

Like Joyce Carol Oates, a number of writers felt they had been mentored not by people but by specific books or a writer’s oeuvre. Samantha Hunt, Denis Johnson, ZZ Packer, Anita Shreve, and Martha Southgate offer not only their lucid memories of encountering these works but a booklist you’re not likely to find anywhere else: The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake, Fat City by Leonard Gardner, the short stories of James Alan McPherson, That Night by Alice McDermott, and Harriet the Spy, respectively. Michael Cunningham, who identifies Virginia Woolf as his muse, wrote about the lifelong companionship Mrs. Dalloway has given him, “a devastating if oneway friendship” that led him to write The Hours when he was in his forties.

Another group of writers had something entirely different in mind in response to my invitation—and I was so eager to read their essays that I happily went beyond the boundaries of the title. Five people wanted to write about institutions or extended periods of their lives that had changed everything—altered their ambitions, rearranged their sense of who they were, what they were capable of, and what they wanted. Jane Smiley dove back into her first year as a graduate student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, 1974, and the influence of her classmates, including Allan Gurganus. Christopher Castellani examined what nine summers at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference have meant to him, beginning with two summers as a waiter. Neil Gordon recollected two transformative years as an editorial assistant at The New York Review of Books, while he finished his doctoral dissertation and charted his ambivalence about writing fiction. Dinaw Mengestu, born in Ethiopia and raised outside Chicago, ran an after school program in Harlem while he licked his wounds at not being able to sell his novel, and learned anew the power of storytelling in his efforts to entertain and soothe his students. Caryl Phillips, born in St. Kitts, raised in Leeds, England, and now a professor of writing at Yale, takes a long look backwards in “Growing Pains,” isolating moments that moved him in the direction of a literary life.

This anthology came into being on the night of March 17, 2008, hours after I submitted an essay to Tin House on my mentor, Elizabeth Hardwick, who had died three months before and with whom I had had a senior tutorial at Barnard Co...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherState University Press of New York

- Publication date2012

- ISBN 10 1438443501

- ISBN 13 9781438443508

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages296

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 12.74

From United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Mentors, Muses & Monsters: 30 Writers on the People Who Changed Their Lives

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Brand New. reprint edition. 279 pages. 9.25x6.25x0.75 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 1438443501

Mentors, Muses & Monsters: 30 Writers on the People Who Changed Their Lives (Excelsior Editions) [Paperback] Benedict, Elizabeth

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.85. Seller Inventory # Q-1438443501