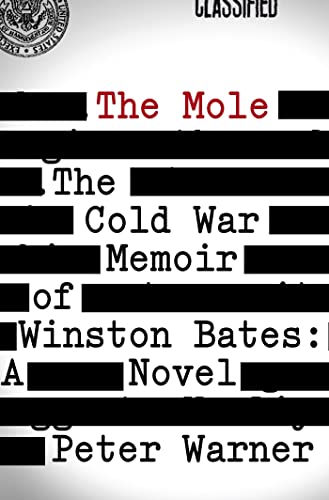

Items related to The Mole: The Cold War Memoir of Winston Bates: A Novel

The fictitious memoir of an unlikely foreign spy planted in Washington, D.C., in the years after World War II

Recruited by a foreign power in postwar Paris and sent to Washington, Winston Bates is without training or talent. He might be a walking definition of the anti-spy. Yet he makes his way onto the staff of the powerful Senator Richard Russell, head of the Armed Services Committee. From that perch, Bates has extensive and revealing contacts with the Dulles brothers, Richard Bissell, Richard Helms, Lyndon Johnson, Joe Alsop, Walter Lippman, Roy Cohn, and even Ollie North to name but a few of the historical players in the American experience Winston befriends―and haplessly betrays for a quarter century.

A comedy of manners set within the circles of power and information, Peter Warner's The Mole is a witty social history of Washington in the latter half of the twentieth century that presents the question: How much damage can be done by the wrong person in the right place at the right time?

Written as Winston's memoir, The Mole details the American Century from an angle definitely off center. From Suez, the U-2 Crash, the Bay of Pigs, Vietnam, and Watergate, the novel is richly and factually detailed, marvelously convincing, and offers the reader a slightly subversive character searching for identity and meaning (as well as his elusive handler) in a heady time during one of history's most defining eras.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

PETER WARNER grew up in New York and graduated from NYU. For many years he worked as a publisher and editor at a book publishing company in New York and London. He is married with three children and has lived in Hoboken, New Jersey since 1987. A previous novel, Lifestyle, was published in 1985.

On April 28, 1953, I quit my job as a cataloguer in the map collection of the Library of Congress. After work, I met Robert Cage, my only friend at the Library, at a dreary bar on the other side of Folger Park. Robert had first acknowledged my existence three years before, a month after I started at the Library, when I came to work wearing my baggy Parisian flea market suit with a plaid flannel shirt and a tie. “What are you supposed to be?” he said in a flat, expressionless tone. “A poet manqué?” He was right; it was the poet’s outfit, circa 1950. But Robert was dressed almost identically, and if he had smiled I would have taken his challenge for a bit of ironic humor. But he just stared at me so I said, “Manqué see, manqué do.” I was rather pleased with myself but I got no reaction from him. I must have made some impression, however, because the next time we ran into each other he asked me to sleep with him. When I told him that I wasn’t homosexual, he said: “If I made this mistake, imagine what everyone else must think.”

“Let them,” I said indifferently, though of course I cared. Robert didn’t care what anyone thought of him. We were both marginal people but I was frustrated with my status while he cultivated his nondescript quality. He had dead-white skin, drab brown hair, and bland, impassive features. He wore heavy-soled black work shoes and brought his lunch to the Library in a metal lunch pail. A brief twitch at the corner of his mouth sufficed for his rare smile or frown. A trace of snide insinuation in his voice was his only inflection. I was jealous of his deadpan style though I was too self-conscious to emulate it. We would sometimes take the train together to New York for a weekend. My twin sister, Alice, had moved to New York at about the same time I moved to Washington and I would stay with her and go to the opera and museums. Robert would spend the weekend drinking and going to jazz clubs. During the return trip he would mock my taste for mandarin culture.

“What did Burnson say when you quit?” Robert asked. He was referring to our supervisor, whose attachment to his collections of fire maps and Colonial America maps was pathological.

“It took him a while to realize that I was quitting,” I said. “He couldn’t believe that anyone would choose to leave his little world of maps. The only thing he cared about was whether he would be allowed to replace me.”

I hadn’t actually told Robert what I was going to be doing. He was staring at me in his disconcerting way: his face frozen, his pale eyes fixed intently on mine. It was a look that often impelled people to babble on until he gave some enigmatic hint of approval. But I was immune today.

Finally Robert said: “I imagine they won’t let him replace you for a while. You’ll be good for the budget.” He ordered another whiskey. “And you’re going to be…”

“I’m going to be on Senator Saltonstall’s staff.”

There was a long pause while Robert gathered his imperturbability. I could read his mind: This was a big step for me.*

“Onwards and upwards,” Robert said drily. “That project of yours on the Massachusetts Bay settlement maps seems to have been opportune.”

For a moment I felt exposed: Had my motives been so obvious? “It’s mainly research and some speech writing. Are you surprised?”

“Mildly. I had assumed you were on your way to becoming a Library lifer.” Robert’s disappointment in himself for underestimating me was probably as close to congratulations as I would get from him. “Does Saltonstall know that you’re still a Canadian citizen?”

“Of course. He even promised to expedite the citizenship process. He can put through a private bill for me.”

“It’s just as well that you’re out of here. Once they root all the lefties and perverts out of the State Department, who knows where they’ll turn? They’ll probably start in on the Library. And they’ll have a field day here. Like shooting fish in a barrel. Not that you’d have been in any danger—despite Burnson’s suspicions—but they could get me on both counts.”

“Don’t worry. Nobody cares about the Library.”

Robert regarded me with sour contempt. “Oh you’re a fool and you’re leaving a fool’s paradise.” Robert ran his hand through his hair, as emphatic a gesture as he allowed himself. “They’ll go after the Library too. It doesn’t matter where you work. Like that poor sucker Harris from the Voice of America. And you read those stories about Cohn and Schine in Europe.” Roy Cohn and David Schine had just concluded a faultfinding trip across Europe, which mostly consisted of holding press conferences in various foreign capitals to cavil about how few copies of The American Legion Magazine there were in American embassy libraries.

“At least I won’t have to worry about being threatened by Cohn on the sex front,” Cage said. “Since I’d have no qualms about threatening back.”

It was the first allusion I had ever heard to Cohn’s homosexuality. “You and Cohn? Are you serious?”

“A poignant encounter in Rock Creek Park. Memorable only for the fact that it was Cohn.”

“I think I’m going to meet them tonight. Or Cohn anyway. I’m going to a party at Elizabeth Boudreau’s home. Cohn is supposed to be there.”

At this he raised his eyebrows, which felt to me like a triumph. “And I took you for a silly boy. All this time you have been calculating your future. And now you’re not only off to the Senate, but also entering sophisticated Washington society. All those questions you had about her … you weren’t so casually curious after all.”

Robert was quite drunk. I had been careful to have only one drink because I wanted to be alert at the party later. I stood up and said good night. “Keep in touch,” Robert said and waved to me with his hand high above his head, as if I were sailing away. And I was. It was the first time in three years that I believed I was fulfilling my purpose in Washington. I had felt helpless until now, unsure how to move to some useful vantage point. But when Saltonstall asked my map division to do a favor for the Massachusetts Historical Society, I leaped at the chance and contrived a couple of personal encounters with the senator. He took a shine to me, especially after I showed off my amazing memory by naming all the ships and their captains of the Great Migration, which had carried Saltonstall’s ancestors to the Bay Colony.

* * *

After leaving Robert, I took a trolley to Dupont Circle and then walked across the P Street Bridge to my little garret apartment in Georgetown, which was only six blocks away from Elizabeth Boudreau’s mansion.

A lot of shameless maneuvering had gone into my invitation from Elizabeth—almost as much as had gone into my new job. I met Elizabeth at St. Thomas Episcopal Church of Georgetown, in whose chorus I had volunteered to sing with the very intention of meeting someone like her, as well as some of the government and military figures who seemed to be active at the church.

Elizabeth Boudreau stood out in the chorus. She had a tinny voice and a propensity for missing entrances and singing the wrong words, but she underwrote the choral director’s salary. After some research, I decided to cultivate her. She was a girl from a destitute but “good” southern family who had married Bob “Butch” Boudreau, a Louisiana lawyer. Though not rich or well bred, Boudreau’s avaricious drive promised to revive her sapless family tree. He was an advisor/sidekick to Huey Long, and he and Elizabeth had arrived in Washington in 1933, when she was eighteen. After Long was assassinated two years later, Boudreau stayed on in Washington as a lobbyist for Standard Oil until 1942, when he went off to war. A year later, Boudreau was killed in Italy. Back in Washington, Elizabeth discovered that her estate included several thousand acres of prime oil-producing land in Louisiana. Soon it included a magnificent house in Georgetown.

I did what I could to make Elizabeth notice me. I became the choral director’s favorite because we shared a mutual contempt for the Metropolitan Opera’s ragged chorus. Once the director began holding me up to the others as an example of error-free singing, I plotted to run into Elizabeth in Georgetown. The first time I said hello to her, in a florist’s shop, she didn’t recognize me. But the second time, when I just happened to be passing by as she was leaving her home one morning, occurred the day after a rehearsal during which I had ruined her solo by loudly launching into her part. Again she didn’t recognize me, but this time I approached her and apologized for my blunder. After that we began to chat occasionally during rehearsal breaks. I doubt if I made much of an impression. Although Elizabeth was hardly an A-list hostess in 1953, I was a drone for the Library of Congress and of less than even passing interest. My break came when I mentioned my research on the Bay Colony settlement maps, which I was doing for the Massachusetts Historical Society at Senator Saltonstall’s request. She seemed uninterested, but a few days later she ran into Saltonstall, dropped my name for want of anything better to say, and learned that I was soon going to be a member of his staff. When she called to invite me, I thought at first it was Robert Cage, in drawling falsetto, playing a practical joke.

For the next thirty-five years I would prepare my agenda for the evening as I walked to Elizabeth’s great house in Georgetown. I would decide whom I wanted to meet, what I wanted to learn, what gossip I wished to catalyze at the party. This first night my plans were modest: I hoped to elicit at least one minor indiscretion to pass on to my undeclared watcher, should I ever be asked. As I walked, I rehearsed little speeches—clever things to say about the Library and self-deprecating remarks about my life, which I hoped would be mistaken for false modesty.

I was greeted at the door by a butler and conveyed to Elizabeth in the drawing room, which was decorated then in a clunky version of veranda colonial. Some thirty guests had arranged themselves in small groups. Elizabeth was seated on a large sofa; with her dress splayed in a circle about her she looked like a taffeta water lily. When she saw me, she motioned assertively for me to approach her. She was small boned and blond, with delicate features and piercing blue eyes. A pale flight of freckles softened her sharp features and gave her a girlish appearance. Standing before her was a fat man with a blotchy face whom she introduced in her gentle southern accent as Arthur Barker, a fellow southerner and a member of the new administration. I recognized the name: He was a protégé of Charles Wilson, the secretary of Defense. “Arthur, Winston sings in the chorus…” She paused waiting for Barker to nod. “… at St. Thomas, you know, the church?… And he just about knows more about music than anyone.” Elizabeth spoke in a fluent succession of semi-queries; by the time you had nodded politely three or four times, she would assume you agreed with whatever she was saying. “Arthur has just rented a house in Georgetown … on O Street?… not far from the university. Arthur was just asking me … you know of course they’re trying to desegregate the public swimming pool over on Twenty-ninth Street?”

Barker, encouraged by their mutual southernness, shook his head in disgust at the prospect, but I was pretty sure Elizabeth had reasonably liberal ideas about these issues. I decided that Elizabeth and I would gang up on stuffy Mr. Barker. “I don’t swim myself, but I do think it is about time for us to let little white children and little dark children inhabit the same water,” I ventured.

Elizabeth continued as if I had not uttered a word. “I can’t tell you how important it is that they get the Georgetown pool desegregated immediately.” Barker looked baffled and I smiled complicitly. “You know they just desegregated the Rosedale pool?” she went on. “That leaves Georgetown as the only white pool. This neighborhood is going to be crawling with white riffraff all summer. The pool will be a magnet. But if they desegregate the Georgetown pool, hardly anyone will come—Negroes can’t swim and the white trash will stay away.” She looked from me to Barker fiercely, her piercing blue eyes and sharp features challenging us, and then she chortled, delighted to have enmeshed us in her unique logic.

I sensed I had failed my first trial of socializing but Elizabeth appeared not to notice. We went on to discuss other aspects of Georgetown life at which I was more successful. When drinks arrived, Elizabeth used the interruption to introduce me to an obtuse woman who managed Oveta Culp Hobby’s office. We discussed Call Me Madam though I was unable to tell her what Perle Mesta was really like.

Almost everyone at the party was someone else’s assistant or aide. I didn’t know why Robert had referred to Elizabeth’s salon as sophisticated, though I soon learned she was trying to live that reputation down, playing it safe with a new administration in town. By the end of the Eisenhower years Elizabeth would be enshrined as an A-list hostess and there would be no more invitations for B- and C-list types except for her biannual Thanksgiving Day buffet party. Elizabeth approached me again with a proud smile on her face and a small spidery woman on her arm. “Winston, my literary friend, I have a surprise for you. I want you to meet Ayn Rand.”

“You are a writer too,” Rand declared. She had one of those gruff, metronomic middle-European accents.

I had rehearsed an amusing little speech about becoming a failed poet in Paris in my foolish youth three years before. But some residual literary pride prevented me from trotting my failure out before another writer. “Actually, Miss Rand, I really think of you as a writer-philosopher.”

“Like Burke,” she said.

I took that as an invitation to explore her ideas but I was spared by the arrival of Roy Cohn. Rand spotted him across the room. “He’s here. I have so much I must tell him.” She deserted me without another word.

Cohn too was somebody’s assistant, but his arrival riveted the party. His European boondoggle with Schine had gotten a lot of bad press though I had the feeling Cohn didn’t care. He was sleek and dark and his baggy baleful eyes measured us with sour expectation. The other guests half turned to glance at him surreptitiously as he spoke to Elizabeth, who was in a state of hostess apotheosis at his presence. I watched Rand zero in on Cohn across the room. She didn’t waste any time; she grabbed at his jacket and Cohn flinched. At that moment dinner was announced and Elizabeth led Cohn into the dining room while Rand scuttled along trying to keep Cohn’s attention. As we were sorting out our assigned places, I saw Rand corner Elizabeth. Later I learned she had prevailed upon Elizabeth to change the seating so she could sit with Cohn. There were four tables of eight and Cohn and Rand wound up at my table. I was seated next to Oveta Culp Hobby’s executive assistant.

Rand didn’t waste a minute of Cohn’s time with small talk. “I have wanted to meet you for such a very long time. Have you heard about the work we have been accomplishing in Hollywood?” She pawed at Cohn’s arm again. “We have had many serious meetings with studio heads. We have a newsletter that—”

“Who’s ‘we’?” Cohn asked while he looked around the table.

Rand looked startled. “You have had a brochure from me. With a letter. That is why I am in Washington. We are the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals. Within a year there will be no films made that do not present a positive depiction of capitalism.”

“Not even ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherThomas Dunne Books

- Publication date2013

- ISBN 10 1250034795

- ISBN 13 9781250034793

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages368

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Mole: The Cold War Memoir of Winston Bates: A Novel

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks436415

The Mole: The Cold War Memoir of Winston Bates Warner, Peter

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.2. Seller Inventory # Q-1250034795