Items related to Saving Baby: How One Woman's Love for a Racehorse...

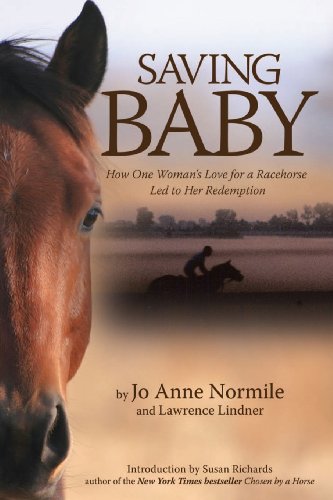

Few people ever call up the courage to create the life they envision, leaving their dreams forever unfulfilled. But Jo Anne Normile did just that, only to find she was living the wrong dream. It all started with her beloved horse Baby, with whom she shared as strong a bond as a mother and child. Baby could be hundreds of feet away, on the far side of the pasture behind the house, but if he saw Normile coming through the kitchen door, he'd leave off grazing on the rich summer grass and come toward her. If she clapped, he broke into a gallop to reach her faster. He loved rubbing his head against her hands. She, in turn, would kiss that velvety part of his muzzle between his nostrils. It was difficult to let him go to race at the track, away from her pasture, from the back door where she'd often find him waiting for a tasty snack or to say hello. But she had made a promise to the man who sold him to her. And on television at least, horseracing had always come across as a glamorous mélange of mint juleps and celebrity set against a backdrop of equine grace and speed. It was a vision Normile liked. What could be a better nexus of beauty and brawn than a blanket of red roses thrown over a shimmering Thoroughbred while his owner held the trophy? But as she gradually learned, the magic that enchants is a veneer. For every Seabiscuit, there are tens of thousands of racehorses whose experiences on the back lots of the country's tracks tell a different, often harrowing, story. It's not that Normile didn't experience a thrill every time Baby sprinted around the track. She fell hard for the adrenalin rush of gleaming, well-muscled horses running faster than any other animal in the world as they cover distances of a mile or more, her heart rising to her throat each time Baby drove into the homestretch turn. The Sport of Kings, as it is known, is like a drug, an intoxicating ecstasy, that transfixes. But once Normile learned the truth, she did a complete about-face, even pulling from the racecourse a promising granddaughter of Secretariat poised to win no small amount of money. And she transformed her misgivings into the pursuit of an entirely different vision, founding the most successful horse rescue in the country and saving more horses than anyone else ever has. SAVING BABY, a memoir, tells her life-changing story of love, regret, and redemption.

Note: A portion of the proceeds from each purchase of Saving Baby goes to Saving Baby Equine Charity, a horse rescue. Learn about the horses you've helped save at: savingbaby.org

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Lawrence Lindner is a New York Times best-selling coauthor and collaborating writer on a wide variety of books ranging from memoirs to animal care to health topics. He also penned a nationally syndicated biweekly column in The Washington Post for several years and wrote a monthly column for The Boston Globe. His freelance work has appeared in publications ranging from The Los Angeles Times to Condé Nast Traveler, the International Herald Tribune, Reader’s Digest, and O, the Oprah Magazine. Currently, he serves as executive editor of Your Dog, a monthly publication of the Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University, and as secretary of Saving Baby Equine Charity.

CHAPTER ONE

It’s very quiet in the barn at night, but when a horse is about to have a baby, she’ll get restless and start to pace, and I wanted to be able to hear the rustling of the straw as Pat walked back and forth. That’s why I started sleeping with my head right next to the video monitor on the coffee table that streamed in the activity from Pat’s stall, the volume turned all the way up.

To catch a mare foaling is rare. Horses almost always give birth in the predawn hours, preferring to have their babies away from people, and even other horses. Some will tell you they can time their labors for privacy. But once their contractions begin, they can’t hold back. And I needed to be there, as a midwife for Pat as well as for myself.

The first couple of nights, Pat didn’t settle in but kept walking and biting at her sides—a sign of pain. She also swished her tail, yet another sign of discomfort.

Then, one night, some time before sunrise, she went down on her side, nipping at her flank. Her pain had increased significantly. She rose, circled several times, then went down again. Her body gave a heave. “This is it, everybody!” I called out, jumping up from my perch on the family room couch and running to the bottom of the staircase. “Grab your stuff!”

We had very little time. A horse gives only three or four major pushes before birthing her foal. The four of us raced down to the barn. My husband, John, would be on duty with the video cam, while one daughter had a camera for still shots and the other would stand by the barn’s wall phone in case there was an improper presentation at birth and the vet needed to be called. Normally a foal is delivered with the front feet coming first, one several inches ahead of the other so that the shoulders, emerging at an angle, can fit through the pelvis. You see the hooves, one before the other, and then the nose laid down on top of the legs. Any other presentation can prove a life-or-death emergency for mare, foal, or both.

We were whooping excitedly, all smiles and eager chatter as we ran from the house, pulling on our coats. We had already seen the baby kick when Pat drank cold water. We loved watching Pat’s stomach sway like a pendulum in her last week before delivery. We had placed bets on whether the foal would look like its mother, with her dark coat, or whether it would have any markings. New life now just moments away, it was a giddy anticipation.

When we reached the barn I had to tell everyone to lower their voices to a whisper. “No running,” I said. We needed to tiptoe, contain our excitement, so Pat wouldn’t be alarmed or disturbed. The baby’s front legs were already out. We could see its knees. We could see the bluish white sac, a filmy casing, enveloping the tiny foal.

By the book, you’re not supposed to go into the stall. Birthing is something horses are meant to do by themselves. But Pat and I were already too bonded. The day we met, she had blown out through her nostrils to greet me, as horses do. She let me touch my face to her muzzle and blow directly into her nose so she could become familiar with my scent. And while some Thoroughbreds are very fine boned, Pat was a big, broad-chested mare with a look more like that of a Quarter Horse, which I preferred. More than that, she was such a people horse. Her eyes beamed empathy, intelligence. So of course I couldn’t let her go through giving birth alone. I went in, knelt down, and stroked the side of her head as she lay there in labor, then moved closer to where the baby was emerging.

But Pat soon rose and started to walk around. The foal needed repositioning to be properly birthed, and Pat’s movement would make it happen. “It’s okay, Pat,” I whispered soothingly while stroking her some more. “I’m here. Everything’s okay.”

Pat shortly went down again, gave a sigh followed by another heave, and out came the foal’s knobby shoulders. They are the widest part of the birth, so we knew we were home free. One more heave, one more sigh, and whoosh, the baby was fully born. It took all of five or six minutes. Elated that we made it in time, we wanted to scream but just kept saying softly, “We have a baby. A baby!”

I was admiring the newborn foal in its sac, adoring its lashes, its tiny feet, when I suddenly realized that the water hadn’t broken. I had been so absorbed in what lay before me that I forgot the hooves are supposed to tear open the sac upon delivery. The baby was in danger of suffocating. A foal needs air once it is out of its mother’s body, just like a person.

“Oh my God!” I cried out, tearing at the sac with my fingernails. But the bluish-white shroud was like tough tire rubber. I was out of my mind with fright and desperation—and guilt. Not only had I wasted time looking at the baby through its sac, lost in awe over its beautifully closed eyes and its rounded forehead, like that of a human newborn. I had also forgotten to store a knife or other sharp instrument in the foaling kit even though I knew about the rare case in which parting the sac needs a human assist.

Finally, I did manage to break open the sac, and water gushed everywhere. I pulled out the foal’s head, but it didn’t start breathing. The newborn remained limp.

Frantic, I cleared the horse’s nose and mouth of mucus, then fastened my mouth on its nostrils and exhaled deeply, expressing air into its lungs. Still nothing. The girls were crying. John and I were, too. You can hear me on the videotape saying, “I think it’s dead.”

The moment, gone disastrously awry, had been more than a decade and a half in the making.

Eighteen years earlier, almost to the day, the legendary Secretariat won the Kentucky Derby. The great Thoroughbreds who run in that race are magnificent beings—powerful yet graceful, and beautiful. I always looked forward to watching the Derby. But my fever spiked in 1973, when Secretariat won not only that run but also the other two races in what is known as the Triple Crown: the Preakness, held in Maryland, and the Belmont Stakes in New York. Two other horses won all three races in the Triple Crown after Secretariat, but it didn’t matter. He was the superhorse; his record times still stand today.

I soon began collecting Secretariat memorabilia—Christmas ornaments, a program from the ’73 Derby, numbered collector plates signed by his jockey. In 1988, we were even able to meet the great stallion. We were driving to Disney World, and our route from our home in Michigan went right through Kentucky, only twenty miles from the farm where Secretariat was living out his life as a stud horse. We took a detour in hopes of catching a glimpse of the magnificent steed.

But when we reached the farm, a groom actually led me right to him. He brought Secretariat out of the barn for me, and I lay my head on his strong shoulder. Surprised by how moved I was, I cried while John and the girls took pictures. I then scratched his mane, as horses will do for each other with their teeth. He was exceptionally well behaved—and massive. “Locomotive” was the word that came to mind, and I thought, “here is the most powerful horse I’ve ever seen.”

Just one year later, Secretariat was euthanized at the relatively young age of nineteen. He suffered from a disease, laminitis, that causes swelling inside the wall of the hoof, increasing pressure on it and making it excruciatingly painful even to stand, let alone walk or run. I’ll never forget the day I heard the news on the car radio.

It was around that time that Secretariat’s owner, Penny Chenery, gave a speech at the Michigan Horse Council’s Annual Stallion Expo, and I learned that one of Secretariat’s sons, a stud horse, lived only a two-hour drive from us. I thought, what better memorabilia could I have than to look out every day and see a grandchild of Secretariat sired by that stallion? I’d have a piece of Secretariat in my own backyard.

By that point we had owned horses of our own for only five years. I had been one of those girls who grew up crazy about horses but never could have one. The feeling never dissipated, and when I turned thirty-six, I convinced my husband to move from our bustling suburb to a home in the country with a barn and pastures. We were not wealthy people—John worked for Michigan Bell and I was a freelance court reporter—but we sold our house at just the right time, for two and a half times what we paid for it, to be able to afford the new one, and then bought two lovely horses in short order. The first was a black Quarter Horse I renamed Black Beauty, giving into a childhood urge. The second we named Pumpkin because of the orange highlights in her coat.

It was an idyllic life, one that should have been enough. From almost every window, beautiful pastureland spread to the tree lines. I could work on my court transcripts, look outside, and take in a view of the horses. I could stop working at my computer at any time and go pet them, or hop on without a saddle and take a short ride to clear my mind. I could finish my work at midnight. It didn’t matter, as long as I met my deadlines.

But the idea kept tugging at me to increase our “herd” with a grandchild of Secretariat. I couldn’t get it out of my head.

Pumpkin was too old to bear a foal by that point, but not Beauty. So I sent her up to be bred to Secretariat’s son. But Beauty miscarried—twice. And each time was an expensive try.

After the second failed attempt, someone at the breeding farm suggested, “Why don’t you lease a mare? She’ll go back to her owner once she delivers the foal, but the foal will be yours. You might as well lease a Thoroughbred. That way, the foal will have papers that will enable you to get it registered with the Jockey Club.”

“I don’t know anything about registering a Thoroughbred,” I said. “I don’t want to race a horse.” It was true. While I loved to watch the Kentucky Derby, I had no ambition to race. I simply wanted to have a grandchild of Secretariat grazing behind my house, like a snow globe come to life.

“But a horse registered with the Jockey Club will always be more valuable,” I was told. “It’ll serve you well should you ever have to sell or trade it.”

So I started making some phone calls to Thoroughbred racing farms. My vet ended up approving a Thoroughbred, Precocious Pat, a dark mare with some reddish hairs around her muzzle who was due to give birth very soon. Pat’s owner, Don Shouse, was sick. He had had a heart attack, and he asked me to take his mare to our house to have the baby. The plan was that I would raise the baby for six months. At weaning time, by which point Don was expected to recover, I’d give it back to him. But I would be allowed to use Pat to breed a horse of my own with the sire of my choosing—Secretariat’s son. I wouldn’t have to pay to lease her since I would be taking care of her and her new baby for a while.

I said yes to the arrangement, and Pat and I took to each other right away. We immediately set up a large stall in the barn in which Pat could have her foal, making room by storing much less hay than we usually did—100 bales at a time instead of 400.

It was in that stall that before us now lay the baby horse’s wet, lifeless body. Though I’d known from the start it wasn’t going to be mine—this was the horse I’d have to return to Don before Pat could be bred to Secretariat’s son—my heart had already laid claim to this baby and its mother. I thought of performing compressions on its chest, but I knew that wouldn’t have been the proper procedure. Besides, a just-birthed foal is so tiny, so vulnerable. It weighs only about 100 pounds the moment it’s born—all bone, with its body narrowly compressed. I was afraid I’d hurt it.

Miserable with my lack of options to pump life into the fragile newborn, I turned back to Pat to see how she was doing. She was trying to see around me, not aware yet that her baby was dead. Then, perhaps thirty seconds later, well after I had tried breathing into the horse’s lungs via its nose, one of the girls cried out, “It’s moving!”

The baby horse’s head stirred ever so slightly. I leaned over for a better look at its sides and saw the in and out of the breathing. The baby was alive!

I went back down and blew into its nose a second time to assure continued respiration, and also as a sign of affection. I wanted the horse to know my scent. That’s what the mare does, and I aimed to mimic her behavior so the foal would associate me with the beginning of time, or at least the beginning of its time.

It was kind of cold—the middle of the night in early May—and the foal was still wet and also shaking, so I hurriedly finished pulling the sac from around it and vigorously dried it with towels. I then waited for the placenta to come out and put it in a pail of water for the vet to inspect. If even a small part of the placenta isn’t delivered, the mother can get an infection, just as with people.

Pat gave her maternal nicker, a soft, barely audible sound that all mares make to their newborns. The intimate message means “Come a little closer,” and the foals respond to it immediately from birth, without any learning process. The bond between mare and foal is so strong, in fact, that animal behaviorist Desmond Morris once wrote about a case of a young horse who was taken from its mare and transported five miles to a place it had never been before, yet managed to find its way back to its mother in five days.

At the sound of the nicker, the baby lifted its head, its ears flopped to the side. It then let out a whinny, although it was more like the honk of a Canadian goose, and that, combined with our relief, I think, made all of us laugh hard.

I got out of the way so Pat could lick her foal’s face and body, inspect her newborn, bond with it physically. About ten minutes later, I said, “We forgot to even look to see if it’s a girl or a boy.” So, just before the baby attempted to stand, I spread its legs. It was still soaking wet underneath from being born, but I could see there were no “attachments.”

“It’s a girl! It’s a girl!”

We watched the wonder of the newborn foal repeatedly trying to stand on its spindly legs until finally succeeding, only to fall again seconds later. It’s no act of futility. It’s an equine Pilates class. With each attempt, a foal’s coordination increases, as does its strength.

Proud, finally, to stand on all fours, the baby foal let out another honk, much louder than the first, and we laughed once more at our “Canadian goose.”

Then she stumbled around searching for nourishment. She tried to nurse on everything her muzzle touched, from the front and back of Pat’s legs to my own shoulders and face and even to the back wall of the stall. Patient mother that Pat was, she nudged the foal into proper position, and I assisted in helping the newborn locate its mother’s udder, heavy with milk.

Soon the sun was rising, baby tucked up against mare, and it was clear to every one of us, exhausted and exhilarated, that at that moment all truly was right with the world.

Copyright © 2013, 2014 by Jo Anne Normile and Lawrence Lindner

Foreword copyright © 2013, 2014 by Susan Richards

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPowder Point Publishing

- Publication date2013

- ISBN 10 0988878003

- ISBN 13 9780988878006

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages274

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 5.45

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Saving Baby: How One Woman's Love for a Racehorse Led to Her Redemption

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. In shrink wrap. Seller Inventory # 100-12549

Saving Baby: How One Woman's Love for a Racehorse Led to Her Redemption

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0988878003

Saving Baby: How One Woman's Love for a Racehorse Led to Her Redemption

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0988878003

Saving Baby: How One Woman's Love for a Racehorse Led to Her Redemption

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0988878003

Saving Baby: How One Woman's Love for a Racehorse Led to Her Redemption

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0988878003

Saving Baby: How One Woman's Love for a Racehorse Led to Her Redemption

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB0988878003

Saving Baby: How One Woman's Love for a Racehorse Led to Her Redemption

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0988878003

Saving Baby: How One Woman's Love for a Racehorse Led to Her Redemption Normile, Jo Anne; Lindner, Lawrence and Richards, Susan

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.9. Seller Inventory # Q-0988878003