Items related to The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in...

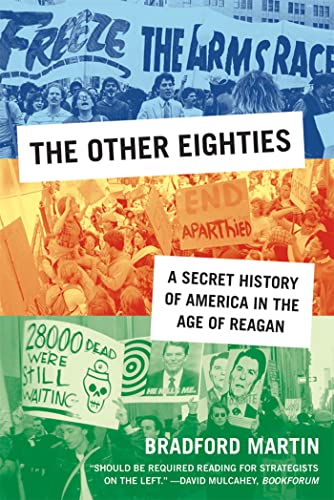

In this engaging book, Bradford Martin illuminates a different 1980s than many remember―one whose history has been buried under the celebratory narrative of conservative ascendancy. Ronald Reagan looms large in most accounts of the period, encouraging Americans to renounce the activist and liberal politics of the 1960s and '70s and embrace the resurgent conservative wave. But a closer look reveals that a sizable swath of Americans strongly disapproved of Reagan's policies throughout his presidency. With a weakened Democratic Party scurrying for the political center, many expressed their dissatisfaction outside electoral politics. Unlike the civil rights and Vietnam-era protesters, activists of the 1980s often found themselves on the defensive, struggling to preserve the hard-won victories of the previous era. Their successes, then, were not in ushering in a new era of progressive reforms but in effecting change in areas from professional life to popular culture, while beating back an even more forceful political shift to the right.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Bradford Martin is an associate professor of history at Bryant University in Rhode Island. He is the author of The Theater Is in the Street: Politics and Performance in Sixties America.

CALLING TO HALT

The Nuclear Freeze Campaign

On June 12, 1982, children and octogenerians were on the march. So were World War II veterans and Tibetans for World Peace. Coretta Scott King and the Bread and Puppet Theater. College students and trade unionists. Movie stars and rock stars. Quakers and Roman Catholic bishops. International pilgrims hailing from such far corners of the globe as Japan, Europe, the Soviet Union, Zambia, and Bangladesh. The total tallied somewhere around three-quarters of a million souls, all making the trek from the United Nations to the Great Lawn of New York City’s Central Park, where the march concluded with a rally for nuclear disarmament. The gathering marked a high point of popular support for the disarmament movement, the largest protest rally in United States history to date. Contemporary observers repeatedly noted its diversity. Phrases like “kaleidoscope of humanity,” “rainbow spectrum,” and “largest, most diverse gathering for a single cause” redounded through media accounts of the event.1 Within that diversity, discernible patterns appeared. The usual suspects on the political left were well represented. Established peace and disarmament groups, from Mobilization for Survival to the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE), organized the event to coincide with the United Nations second special session on disarmament. Peace-oriented religious groups, including the American Friends Service Committee, Pax Christi USA, the Fellowship of Reconciliation, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, loomed prominently among the sponsors. Professional organizations from Physicians for Social Responsibility, to the Union of Concerned Scientists, to the National Lawyers Guild all lent support. Jackson Browne, James Taylor, Bruce Springsteen, Joan Baez, and Linda Ronstadt, musicians with long track records of support for peace and antinuclear causes, all performed.

But though the usual suspects organized the rally, its vast, broad-based assemblage made the Central Park gathering different. The Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign, as the central organization’s official title ran, struck upon a simple and galvanizing idea—for the United States and the Soviet Union to enter a mutual and verifiable freeze on the testing, production, and deployment of all nuclear weapons—and through widespread grassroots activity delivered that message to mainstream America. The campaign drew from all socioeconomic groups in almost every geographic region—and even garnered support from Republicans.

The campaign rode this wave of enthusiasm through the 1982 midterm elections, which saw a number of freeze resolutions around the country succeed in state referenda. After that, the movement declined, failing to translate popular momentum into concrete policy measures and faltering badly with the advent of President Reagan’s Star Wars plan and his 1984 reelection.2 But along the way, the movement wielded more influence than popular accounts suggest, reshaping the foreign policy landscape in which the Reagan administration operated. The saber-rattling Cold Warrior rhetoric of Reagan during his candidacy and the early part of his first administration asked the American public to envision fighting and winning a nuclear war and to commit the necessary resources to building nuclear arsenals to achieve superiority over the Soviets. The freeze campaign pressured the administration to tone down its foreign policy ambitions and encouraged a move toward arms reduction negotiations. It eroded the authority of the high priesthood of defense intellectuals, a group that developed a self-reinforcing idea that nuclear weapons policy ought to remain the exclusive domain of expert insiders who had mastered the highly technical intricacies of ICBMs and MX and Pershing II missiles. It reenergized public discussion about national security by making it more accessible. Most Americans, whether or not they agreed with the idea, could wrap their minds around the concept of stopping the creation of more nuclear weapons as a logical first step to eliminating them altogether. Finally, the movement succeeded in orienting many Americans toward a more internationalist and global peace perspective and away from fixation on the bipolar superpower conflict by exploring common ground between the interests of American citizens and those of people around the world.

The freeze movement combined veteran activist leadership at the national level with a tremendous vitality at the grass roots. From the local pressure of Vermont town meetings passing resolutions to the populist statement of half a million Californians signing a petition, the campaign empowered ordinary people to challenge the national security establishment. It fostered greater awareness of Americans’ interconnectedness with European “neighbors” threatened by the specter of nuclear war, and it represented genuine ferment at the grass roots that surfaced at the level of national politics. Despite the simplicity of its appeal, it failed to achieve its targeted results of stopping nuclear weapons testing, production, and deployment. Though it mobilized new activists by the thousands, its lack of a militant wing, capable of direct action when necessary, encouraged co-optation and discouraged more substantive concessions from national leaders. Priding itself on being a more reasonable, tempered kind of movement that eschewed the excesses of 1960s activism, the freeze movement reflected the resurgence of a consensus-oriented, anti-dissent mood that pervaded the dominant culture of the 1980s. This attitude set limits on the movement’s potency. But against the backdrop of the early Reagan administration’s militant tone and actions, freeze supporters elevated public awareness of peace and disarmament issues, reshaped the dialogue about nuclear weapons, and forced national policymakers to adopt a subtler, less frontal approach to waging the Cold War.

Calling to Halt: Randall Forsberg and the Idea of the Freeze

Though mass movements frequently downplay the importance of individual leaders, Randall Forsberg was the freeze’s most identifiable figure. Forsberg’s arms control career took her from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), to a political science doctorate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to founding the Institute for Defense and Disarmament Studies in 1980. Her experience at SIPRI, an institution dedicated to independent analysis of U.S.-Soviet rivalry, loomed large. There, originally working as a typist, Forsberg discovered that superpower talks over a 1963 test ban treaty had broken down over U.S. insistence on seven inspections a year, while the Russians held the line at three. The experience made her wonder, “Why not compromise on five?”3 This evenhanded, commonsense approach to the Cold War pervaded Forsberg’s intellectual outlook and shaped the freeze’s bilateral approach. It also guided her willingness to confront the arms control establishment’s insular technocracy.

Forsberg crafted the freeze’s seminal statement, “A Call to Halt the Nuclear Arms Race,” to penetrate the nuclear elite’s intimidating culture of expertise. The 1980 document built on the work of groups such as Mobilization for Survival, the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), and the Fellowship of Reconciliation, which had also called for a moratorium on constructing and deploying nuclear weapons. In 1979 the AFSC sponsored a delegation to the Soviet Union, which included Forsberg, to explore the feasibility of this plan. Upon her return, Forsberg revised the freeze idea to maximize its potential to attract support from mainstream America. She conceived of the proposed freeze as a manageable first small step toward further, more comprehensive disarmament initiatives—one that could unify diverse groups of activists and citizens on the way to something much bigger that would ultimately produce a more peaceful world.

Yet against the backdrop of the arms race, a total freeze was no mere baby step. Halting the testing, production, and deployment of nuclear weapons would mean that neither the United States nor the Soviets could add to their stockpiles or improve nuclear technologies to newly lethal levels. Seductively simple, Forsberg’s plan transcended previous arms control proposals by promising first to stop the arms race in its tracks, then to pursue further reductions.4 Proponents of a mutual and verifiable freeze cleverly provided an accessible goal that a broad cross section of the American public could rally behind.

Moreover, the clear language of “Call to Halt” gave activists the confidence to enter the national policymaking debate on nuclear weapons. Contending that “the horror of a nuclear holocaust is universally acknowledged,” the freeze proposal cast the issue as simple common sense. It claimed that the two superpowers possessed upward of fifty thousand nuclear weapons, a stockpile that could wipe out “all cities in the northern hemisphere” in half an hour. With these facts simply stated, “Call to Halt” underscored the excessive nature of plans for the United States and the U.S.S.R. to build twenty thousand more nuclear warheads, along with new missiles and aircraft. Echoing Albert Einstein’s maxim about the impossibility of simultaneously preparing for and preventing war, the freeze proposal claimed that burgeoning weapons programs would “pull the nuclear tripwire tighter,” creating “hairtrigger readiness for a massive nuclear exchange.” Rejecting the logic of deterrence that underpinned three decades of arms race escalation, the freeze idea posited that more nuclear weapons made the world more dangerous rather than safer. “Call to Halt” also invoked the mammoth fiscal savings a freeze would entail, sketching out numerous domestic spending alternatives and a range of attendant social and economic benefits. Finally, the proposal pointed to further steps toward a lasting peace that could be addressed after achieving a U.S.-Soviet freeze, including extending the freeze to other nations and reducing existing nuclear arsenals.

An inspiring document with populist appeal, “Call to Halt” was quickly endorsed by a laundry list of prominent activists, intellectuals, and leaders, including the former undersecretary of state George Ball, the most prominent of President Lyndon Johnson’s advisers to oppose escalation in Vietnam; the former secretary of defense Clark Clifford; the former CIA director William Colby; the former ambassador to the Soviet Union Averell Harriman; and the U.S. Cold War policy architect George Kennan. Scientific community supporters included the two-time Nobel laureate Linus Pauling, the former MIT president Jerome Wiesner, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists editor Bernard Feld, Jonas Salk, and the Cosmos host Carl Sagan. With these and other illustrious names behind it, the movement swiftly gained legitimacy.5

But just as the freeze movement gained popular support, it was forced to grapple with an event that posed a grave threat to its goals: the election of Ronald Reagan. The complex public sentiment that could simultaneously produce a potent statement against nuclear weapons and install a hard-line Cold Warrior in the highest office reflected a transitional moment in national politics. Americans wrestled in a psychic tug-of-war between fear of nuclear annihilation and desire for renewed military might. One New York Times/CBS poll showed 72 percent support for a freeze but hastened to point out that the numbers roughly flipped if such a moratorium froze a Soviet weapons advantage in place.6

Sensing this ambivalence, peace activists recognized the need to develop a systematic approach to organizing, educating, and wielding political influence, and in March 1981 they convened in Washington, D.C., to formulate the game plan. Though excitement pervaded the conference, a set of conflicts emerged among the attendees. Some activists viewed the nuclear freeze as an end in itself, an important and legitimate arms control goal worth striving for; others, including Forsberg, saw it as a discrete, winnable battle that could open up the policymaking terrain for confronting broader issues of militarism. Further, they contended that such a freeze might ultimately transform international relations, especially U.S.-Soviet animosity and suspicion. The competing goals and visions for the freeze raised complex questions for movement strategy as well. If freeze activists wished to use the proposal to confront the arms race and militarism more broadly, this suggested a more militant approach that could educate about the connections, for instance, between the bipolar weapons race and Cold War interventionism in the Third World. On the other hand, if the vision of the freeze as its own prize prevailed, this suggested avoiding larger, more ideologically charged issues, since these risked alienating mainstream supporters who bristled at leftist critiques of militarism that flowed from the ranks of the more radical peace activists.

Ultimately, the conference committed to a tight focus on the main issue and a strategy that emphasized slow, steady education and building grassroots support. Restricting the agenda was a conscious choice, contrary to the wishes of supporters who also wanted a movement that indicted Cold War militarism generally. Though most organizers agreed that the freeze was a legitimate goal, it also represented a lowest common denominator strategy. Steering clear of controversy enough to attract support from mainstream Americans with no previous activist experience, it was “small enough to be achievable, and large enough to be inspiring.” The residue of distaste for the excesses of 1960s-era radical protest, increasingly excoriated and discredited by 1980s media and intelligentsia, hung heavy. Accordingly, the conference’s resolution—a four-phase strategy of demonstrating the concept’s potential, building public support, leveraging policymakers and provoking national debate, and making the freeze a national policy objective—sought to maximize mainstream participation at the grass roots. Freeze organizers wanted to avoid creating a movement where veteran radical peace activists played the central role. As Forsberg remarked, she wanted the movement “very middle class.”7 As it turned out, this strategy succeeded, for better and for worse.

Grass Roots

Independently of Forsberg’s efforts, Massachusetts peace activists led by Randy Kehler of the Traprock Peace Center had been collecting signatures at supermarkets and shopping centers for a state ballot measure calling on the president to propose a bilateral nuclear weapons moratorium. In November 1980, after a summer and fall educational campaign about the arms race and its social and economic impact that included house meetings, study groups, film showings, and school presentations, voters in three western Massachusetts state senatorial districts endorsed the freeze measure by a 3:2 ratio. Kehler, later the freeze campaign’s national coordinator, touted its potential: “The nuclear race transcends party division and conservative-liberal divisions, and this proves that the American public is indeed ready to see the nuclear arms race ended.” Kehler waxed enthusiastic about the possibilities for broad-based s...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHill and Wang

- Publication date2012

- ISBN 10 0809074591

- ISBN 13 9780809074594

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.25

From Canada to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Other Eighties

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Paperback. Publisher overstock, may contain remainder mark on edge. Seller Inventory # 9780809074594B

The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of Reagan (Paperback or Softback)

Book Description Paperback or Softback. Condition: New. The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of Reagan 0.69. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9780809074594

The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of Reagan

Book Description Soft cover. Condition: New. 1st Edition. New Softcover includes Notes and Index, 242 pages. Seller Inventory # 002395

The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of Reagan

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # ABLIING23Feb2416190215997

The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of Reagan

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New! This item is printed on demand. Seller Inventory # 0809074591

The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of Reagan

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 52GZZZ00VT1G_ns

The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of Reagan

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 0.7. Seller Inventory # 0809074591-2-1

The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of Reagan

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 0.7. Seller Inventory # 353-0809074591-new

The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of Reagan

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # I-9780809074594

The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of Reagan

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0809074591